Archives Hub feature for June 2016

29th June 2016 sees the 50th anniversary of the official launch of Barclaycard, the first all-purpose credit card in Europe.

Origins and Idea

The idea of Barclaycard is credited to general manager Derek Wilde, later a vice-chairman of Barclays, and James Dale, who became Barclaycard’s first departmental manager. Their idea was backed by Barclays’ chairman John Thomson, who recognised the need to ‘beat the others to it’. The immediate inspiration came from a visit to the United States in 1965 by Wilde, Dale and computer expert Alan Duncan, specifically to look at Bank of America’s BankAmericard.

Barclays had, since the mid-1950s, begun to innovate and modernise in areas such as technology and advertising, for example ordering the first computer for branch accounting in 1959, and experimenting with cinema advertising. In 1967 Barclays would pioneer the world’s first external wall-mounted cash machines.

The card scheme was approved by the board without any market research or pilot, or adequate in-house computer system, and in the face of not inconsiderable internal and external suspicion, even hostility. It was recognised that profitability would be long-term, since the set-up costs were so high and credit controls strict.

Although the idea of a plastic card for making general purchases was novel in Britain, consumer credit had already secured a place in people’s lives. Working people had long bought essentials ‘on tick’ from their corner shop, and after World War Two the idea of hire purchase was developed into big business, becoming an integral part of the ‘affluent society’.

The most successful outlets in the early period, despite a very low profit margin, were petrol stations, whose proprietors envisaged improved security in reducing the use of cash, while Barclays saw advantage in roadside advertising.

Launch

‘The Barclaycard is the largest operation the Bank has ever mounted’, declared Barclays’ staff magazine.

On 10th January 1966 the scheme was announced to the public. The press release shows that Barclays carefully eschewed advertising it as a source of unsecured borrowing. Instead, Barclaycard was described as,

‘a logical extension of the existing commercial bank facilities provided by the Barclays Group. Its purpose is to reduce the use of cash in shopping and other transactions and the scheme is designed to appeal not only to those who must travel and spend a good deal of money in restaurants, but also to the everyday shopper throughout the country. For retail and service establishments it will provide a means of reducing or eliminating the book-keeping now needed to maintain customers’ credit accounts.’

Indeed, Thomson saw Barclaycard as, ‘…more of a development of existing retail banking than an innovation…’ As with automated accounting and cash machines, Barclaycard held a promise for the bank of reducing its labour costs, which, with the advent of relatively full employment and strong trade unions, were rising steadily.

Barclays set itself the daunting task of recruiting 1 million cardholders and 30,000 outlets by the launch date. A derelict footwear factory in Northampton was converted as the operations centre, while £500,000 was spent on advertising and over 23 million forms were sent to prospective customers. Barclays adapted the computer programme used by BankAmericard. Distribution of the 1m cards involved extra Post Office and railway facilities.

Signing up merchant outlets was achieved by an organisational innovation. Dale recruited salesmen, largely selected from the Barclays staff on recommendation by inspection teams and branch managers, who were trained to call personally on prospective merchants. The idea of undertaking ‘selling’ was still anathema to the traditional British banker, but these recruits were often glad to break free of the confines of branch banking and enter the modern world of marketing. External training was also used by Barclays for the first time. In the words of one of the early salesmen,

‘It was all direct selling and it was cold selling in many ways. It was in actual fact, just walking along the streets and just looking at shops and saying, yes, the average sale in that shop is a certain amount, that’s a good average sale.’

Acceptance – the triumph of plastic

Most of the 1.25m unsolicited cards sent to potential users in 1966 were accepted, but some were either returned, destroyed or not used: in 2015 Group Archives was pleased to receive the timely donation from a customer, of her late father’s unused card, surviving in pristine condition from 1966!

Barclaycard steadily secured a place in retail culture. Its first operating profit was recorded in 1972, by which time there were 1.7m cardholders and 52,000 merchants. As another salesman recalled of this period:

‘Well, I would just go and say, have you ever thought of taking Barclaycard? It was such a strong product then that they either said yes or no. And if they said yes, you’d sign them up and if no, you’d go into the next shop. It was so easy to do then.’

The move towards a plastic credit society was cautious in the early years. When in November 1967 (following relaxation of the government’s credit squeeze), Barclaycard granted extended or revolving credit to holders, this was done on the understanding (with the Bank of England), that the card could not be used to acquire credit for more than 3 months, and that advertising would be suspended pro tem. This, it was recognised by Barclays at the time, was the only way that the card would ever make a profit. In effect card holders had a personal overdraft facility.

Confirmation that credit cards were here to stay came in 1972 with the launch of Barclaycard’s first major rival – Access – by Lloyds, NatWest and Midland.

Advertising

As in other areas, Barclaycard’s marketing was at the forefront of innovation for Barclays and British banking as a whole.

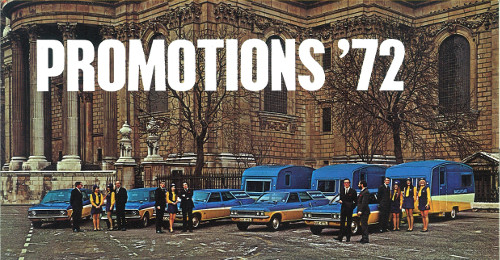

From the start, use was made of modern techniques, including direct mailings and colour magazine adverts. The initial recruitment of holders in 1966 was helped by a mass campaign, including the first direct mail shot by a British bank and a complete list of all the merchant outlets, believed to be one of the largest newspapers adverts ever published. High street campaigns were another radical departure for a Bank:

‘….we would go to a town and set this promotion up with all the retailers. So we picked somewhere big like Brighton or Manchester or Liverpool and you always needed one or two big department stores as a sort of corner-stone, and we persuaded all these stores and shops to display Barclaycard material.’ Barclaycard ‘girls’, hired from an agency and dressed in a uniform to attract attention, would stop people on the street.

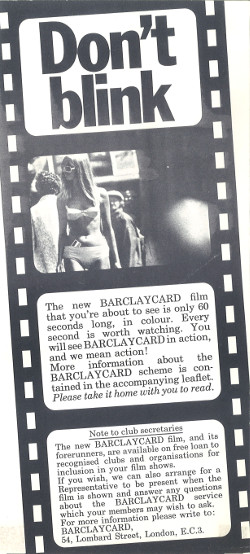

In 1968 an award-winning cinema film, Travelling Light, featured a young shopper with a card tucked into her bikini:

‘ One of my jobs was to make sure that the Barclaycard always showed correctly and so on, so I had the job of positioning it in her briefs to make sure it was all positioned correctly…. It had a very good message, because I think the message at the end was that all you need to go shopping is a Barclaycard.’

Later developments

Although space doesn’t permit an account of Barclaycard’s subsequent history here, it’s worth noting some of the landmarks, several of which have derived from advances in computer and mobile phone technology:

- 1972: first television advert (first for Barclays, too)

- 1973: 2 million card holders

- 1977: Barclaycard a founder of the VISA network

- 1977: Company Barclaycard

- 1982: first in series of Alan Whicker TV adverts

- 1985: 8 million card holders

- 1986: PDQ machines, the first electronic card payment terminals in the UK, introduced to replace manual imprinters

- 1988: Student Barclaycard

- 1990: first in series of Rowan Atkinson TV adverts

- 1990s: expansion into Europe

- 1995: Barclaycard Netlink, the UK’s first bank-related commercial internet service, which soon enabled card holders to pay their bills online

- 1997: introduction of microchips on cards to improve security

- 2001: initial sponsorship of FA Premiership

- 2002: 11 million cards

- 2004: acquisition of Juniper, enabling Barclaycard to expand in USA

- 2007: ‘contactless’ cards, first in the UK

- 2012: PayTag, enabling customers to pay using their mobile phone by sticking a Barclaycard PayTag to the back of their handset

- 2014: 30 million cards

Records and research

‘Plastic money’, a phrase detected in a Barclays report from as early as 1967, has attracted attention from academic researchers in recent years, Barclaycard being cited as an example of technical and financial innovation, marketing success and market leadership.

Most of the documentation of Barclaycard is to be found with the Bank’s main record series. By establishing contacts with the marketing teams, a good representative selection of advertising material has also been captured, and this has been supplemented by donations from former staff members.

Research by Archives staff has established a good framework for the factual history of Barclaycard. For the story of the early years, Group Archives is able to supplement the written record by means of oral history interviews, a few excerpts from which have been quoted above.

In just over a decade from conception in 1965, Barclays successfully embedded the credit card in the retail economy of Britain, an essential payment medium that is taken for granted today.

Nicholas Webb

Archivist

Barclays Group Archives

Related:

Browse the Barclays Group Archives Collections on the Archives Hub

Previous feature: Barclays Group Archives

All images copyright the Barclays Group and reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holder.