=== Browse Barclays Group Archives on the Archives Hub ===

Barclays Group Archives is a living business archive, with material being managed, made available, interpreted, and added to, by a small team of in-house archivists. We encourage external access to our collections, where possible, bearing in mind any necessary restrictions imposed by customer, commercial and third-party confidentiality.

Some history…

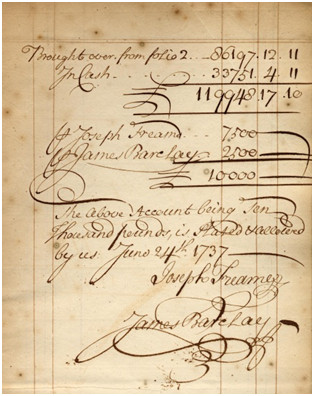

Today Barclays PLC is one of the world’s largest financial services providers, offering banking services to customers in over 50 countries. It has come a long way from its foundation in 1690 by two goldsmith bankers, John Freame and Thomas Gould, in Lombard Street, London. In 1736 James Barclay entered the partnership, and the Barclay name has been a presence in the business ever since. In 1896, 19 smaller banks (all but two being private country partnerships) joined Barclays to form a new joint stock bank – Barclay and Company Limited.

Many of the founding banks had been established by families who were members of the Society of Friends (also known as Quakers). As a result, a business and social network already existed between several of the banks, one that was strengthened by marriage ties. Their Quakerism also helped to contribute towards the success of their banks, as Quakers were renowned for their sobriety and trustworthiness. David Barclay (1728-1809) epitomised the Quaker banker with a social conscience, being active in the anti-slavery movement.

The businesses from which the country banks had developed included brewing, iron trading, shipping and shop-keeping, but the most common route to a successful country bank was via the textile industry. The Gurneys, who had founded their first bank in Norwich in 1775, had originally been woollen merchants. Their banks were spread across East Anglia and accounted for eight of the twenty firms that took part in the 1896 amalgamation.

Similarly, the Backhouses of Darlington established their bank in 1774 on wealth accumulated in linen manufacturing. It was the Gurneys and the Backhouses, together with Barclays, who formed the driving force behind the new bank.

In 1896 Barclays had 182 branches and 806 staff. The next 20 years saw a spectacular series of takeovers, such that by 1920 Barclays was ranked third amongst Britain’s ‘Big Five’ clearing banks and with a national branch network. The new bank was organised into a network of Local Head Offices based on the old head offices of the original partnership banks. This helped to ensure a degree of continuity for customers and the retention of local knowledge and experience built up by local staff and partners.

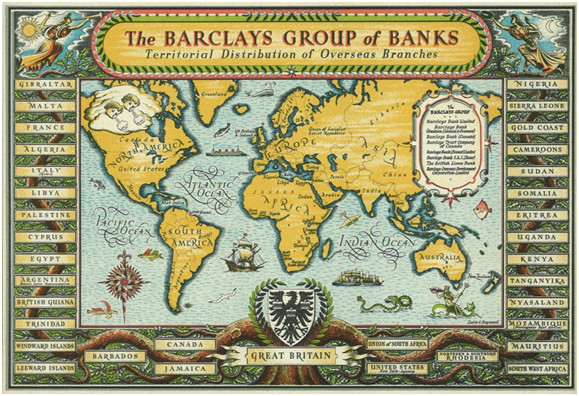

Barclays’ ambitions also lay beyond home shores. Under the chairmanship of Frederick Goodenough Barclays acquired the Colonial Bank, with branches in the Caribbean and West Africa; the Anglo-Egyptian Bank; and the National Bank of South Africa. In 1925 these were brought together to form a new international subsidiary – Barclays Bank (Dominion, Colonial and Overseas). Subsequently Barclays established itself in North America and Western Europe, and in more recent decades has expanded into fresh international fields, with a major presence in Asia and the Gulf.

Barclays has been in the forefront of innovation, introducing the UK’s first cash machines, credit and debit cards; was the first bank to order a mainframe computer for customer accounts, and more recently has pioneered contactless card payments and mobile banking.

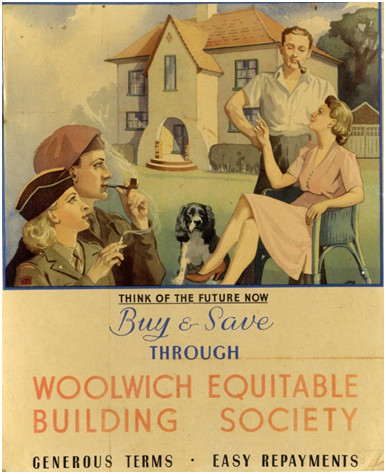

Recent decades have seen two major domestic acquisitions. Martins Bank, acquired in1968, was itself the result of a 1918 amalgamation between Martins Bank of London, which traced its history back to Elizabeth I’s financial agent Sir Thomas Gresham, and the Bank of Liverpool, a new joint stock bank founded in 1831. In 2000, Barclays acquired The Woolwich, a former building society founded in 1847.

In 1986, Barclays established an investment banking operation, which has since developed into Barclays Capital, a major division of the bank that manages larger corporate and institutional business.

Highlights of the Archives…

Noteworthy collections include:

- Barclays partners’ annual balance books, 1733 onwards

- Martins partners’ letter books, 18th century (mentions South Sea Bubble)

- Goslings of Fleet Street: customer ledgers, 1717-1900s: one of a handful of surviving complete banking ledger sets for the 18th-19th centuries

- Private banking partnership agreements and papers, 18th-19th centuries

- Gurney/Barclay letters: social, political and banking life, c1770-c1870

- Complete runs of company minute books from the early days of joint stock banking

- Langton letters (Bank of England and the financial crisis of 1837)

- Bank amalgamation records, 1896 onwards

- Visit and inspection reports, UK and overseas, 19th-20th century

- Staff magazines and internal communications, 20th century

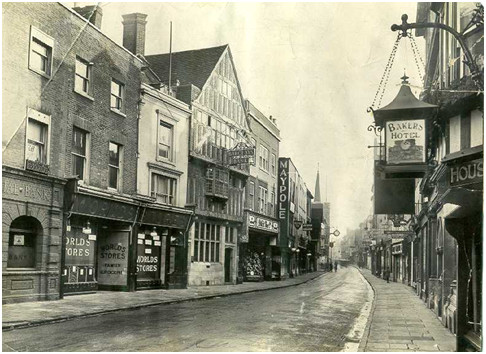

- Photographs of bank premises (including interiors), many showing high street views, over a period of 100 years

- Photographs of overseas bank premises, including views of pioneering bank operations in overseas territories, early 1900s onwards

- Woolwich: one of a handful of readily accessible building society archives, 1847 onwards

Research potential…

As well as contributing to the documentation of British banking over three centuries, the archives offer potential for the following broad fields of research:

- economic history

- company and organization history

- local and community history

- accounting history

- investment

- biography

- commercial architecture

- government regulation

- colonial and post-colonial development

- social history

- employment, training and equal opportunities

- family history

One interesting recent use of the archives has been by two local historians who have for the last few years been examining the income and expenditure of the earls of Warrington during the late-18th and early-19th centuries, contained in our best surviving set of customer ledgers.

Since the archives service was put on a professional footing in 1990 the collections have been used for a broad variety of research, either wholly or as part of wider projects:

- Women in banking and as investors

- Architecture and building history for Buildings of England series

- Furniture commissioned by Clive of India

- Account of Charles Dodgson (Lewis Carroll, author of Alice in Wonderland)

- Clients of Alan Ramsay, 18th century Scottish portrait painter

- History of agricultural finance

- Quaker business and family networks

- Decolonisation and post-colonial development in Africa

- Development of English building societies

- Account of Edward Gibbon, historian

- The usury laws in the 1830s

- Banking philanthropy, 1870-1912

- Banking elites

- Emergence and development of professional accountancy in Libya

- Employee casualties in World War One

- Wallpaper makers, suppliers and their clients, 1700 – 1820

- Evidence for women using heavy machinery, early 20th century

- Terms of business and commercial bank lending in UK, 1885-1925

- International financial regulation and supervision, 1960-1980

- Financial crises at the outbreak of the two World Wars

- Marriage bar in UK employment history

- The public debate about Barclays’ presence in apartheid-era South Africa

- History of commercial advertising

Further information and resources…

Detailed database catalogues are available to consult in person, and bespoke catalogues may be generated on request.

In 2013 BGA has become a contributor to The Archives Hub, and intends to add collection-level descriptions, suitably indexed, to supplement its own detailed database catalogues and indexes.

Official published histories of the Group:

M Ackrill & L Hannah, Barclays: the business of banking 1690-1996 (Cambridge University Press 2001); this volume won the Wadsworth Prize for business history

A W Tuke & R J H Gillman, Barclays Bank Limited 1926-1969 (Barclays 1972)

P W Matthews & A W Tuke, History of Barclays Bank Limited: including the many private and joint stock banks amalgamated and affiliated with it (Blades, East & Blades 1926)

Sir J Crossley & J Blandford, The DCO Story: a history of banking in many countries 1925-71 (Barclays 1975)

[R H Mottram, comp] A Banking Centenary: Barclays Bank (Dominion, Colonial & Overseas) 1836-1936 (Barclays, private circulation [1937])

anon., A Bank in Battledress: being the story of Barclays Bank (Dominion, Colonial & Overseas) during the second world war 1939-45 (Barclays, private circulation 1948)

G Chandler, Four Centuries of Banking: as illustrated by the bankers, customers and staff associated with the constituent banks of Martins Bank Limited (Batsford 2 vols. 1964, 1968)

B Ritchie, We’re with the Woolwich 1847-1997: the story of the Woolwich Building Society (James & James 1997)

see also: J Orbell & A Turton, British Banking: a guide to historical records (Ashgate 2001)

Barclays’ history and archives web pages include:

- summary histories of the Group including major acquisitions – Martins Bank and Woolwich Building Society

- topical fact sheets including: Quaker bankers; Barclays innovations (Barclaycard, Cash Machines; Connect Card – UK’s first debit card); Barclays Eagle logo; Lombard Street; Barclays World

- an illustrated timeline of events

- access conditions and full contact details for Group Archives

http://group.barclays.com/about-barclays/about-us#barclays-history

Nicholas Webb

Archivist, Barclays Group Archives

All images copyright the Barclays Group, and reproduced with the kind permission of the copyright holder.