The recent Digital Humanities @ University of Manchester conference presented research and pondered issues surrounding digital humanities. I attended the morning of the conference, interested to understand more about the discipline and how archivists might interact with digital humanists, and consider ways of opening up their materials that might facilitate this new kind of approach.

Visualisation within digital humanities was presented in a keynote by Dr Massimo Riva, from Brown University. He talked about the importance of methodologies based on computation, whether the sources are analogue or digital, and how these techniques are becoming increasingly essential for humanities. He asked whether a picture is worth one million words, and presented some thought-provoking quotes relating to visualisation, such as a quote by John Berger: “The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled.” (John Berger, Ways of Seeing, 1972).

Riva talked about how visual projection is increasingly tied up with who we are and what we do. But is digital humanities translational or transformative? Are these tools useful for the pursuit of traditional scholarly goals, or do they herald a new paradigm? Does digital humanities imply that scholars are making things as they research, not just generating texts? Riva asked how we can combine close reading of individual artifacts and ‘distant reading’ of patterns across millions of artifacts. He posited that visualisation helps with issues of scale; making sense of huge amounts of data. It also helps cross boundaries of language and communication.

Riva talked about the fascinating Cave Writing at Brown University, a new kind of cognitive experience. It is a four-wall, immersive virtual reality device, a room of words. This led into his thoughts about data as a type of artifact and the nature of the archive.

“On the cusp of the twenty–first century…we speak of an ex–static archive, of an archive not assembled behind stone walls but suspended in a liquid element behind a luminous screen; the archive becomes a virtual repository of knowledge without visible limits, an archive in which the material now becomes immaterial.” This change “has altered in still unimaginable ways our relationship to the archive”. (Voss & Werner, 1999)

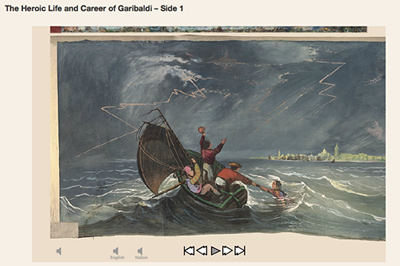

The Garibaldi panorama is a 276 feet long, a panorama that tells the story of Garibaldi, the Italian general and politician.  It is fragile and cannot be directly consulted by scholars. So, the whole panorama was photographed in 91 digital images in 2007. The digital experience is clearly different to the physical experience. But the resulting digital panorama can be interacted with it many various ways and it is widely available via the website along with various tools to help researchers interpret the panorama. It is interesting to think about how much this is in itself a curated experience, and how much it is an experience that the user curates themselves. Maybe it is both. If it is curated, then it is not really the archivists who are curators, but those who have created the experience those with the ability to create such technical digital environments. It is also possible for students to create their own resources, and then for those resources to become part of the experience, such as an interactive timeline based on the panorama. So, students can enhance the metadata as a form of digital scholarship.

It is fragile and cannot be directly consulted by scholars. So, the whole panorama was photographed in 91 digital images in 2007. The digital experience is clearly different to the physical experience. But the resulting digital panorama can be interacted with it many various ways and it is widely available via the website along with various tools to help researchers interpret the panorama. It is interesting to think about how much this is in itself a curated experience, and how much it is an experience that the user curates themselves. Maybe it is both. If it is curated, then it is not really the archivists who are curators, but those who have created the experience those with the ability to create such technical digital environments. It is also possible for students to create their own resources, and then for those resources to become part of the experience, such as an interactive timeline based on the panorama. So, students can enhance the metadata as a form of digital scholarship.

Riva showed an example of a collaborative environment where students can take parts of the panorama that interests them and explore it, finding links and connections and studying parts of the panorama along with relevant texts. It is fascinating as an archivist to see examples like this where the original archive remains the basis of the scholarly endeavour. The artifact is at a distance to the actual experience, but the researcher can analyse it to a very detailed level. It raises the whole debate around the importance of studying the original archive. As tools and environments become more and more sophisticated, it is possible to argue that the added value of a digital experience is very substantial, and for many researchers, preferable to handling the original.

Riva talked about the learning curve with the software. Scholars struggled to understand the full potential of it and what they could do and needed to invest time in this. But an important positive was that students could feedback to the programmers, in order to help them improve the environment.

We had short presentations on a diverse range of projects, all of which showed how digital humanities is helping to reveal history to us in many ways. Dr Guyda Armstrong made the point that library catalogues are more than they might seem – they are a part of cultural history. This is reflected in a bid for funding for a Digging into Data project, metaSCOPE, looking at bibliographical metadata as datamassive cultural history. The questions the project hopes to answer are many: how are different cultures expressed in the data? How do library collections data reflect the epistemic values, national and disciplinary cultures and artifacts of production and dissemination expressed in their creation? This project could help with mapping the history of publishing in space and time, as well as showing the history of one book over time.

We saw many examples of how visual work and digital humanities approaches can bring history to life and help with new understanding of many areas of research. I was interested to hear how the mapping of the Caribbean during the 18th century opened up the coastline to the slave traders, but the interior, which was not mapped in any detail, remained in many ways a free area, where the slave traders did not have control. The mapping had a direct influence on many people’s lives in very fundamental ways.

Another point that really stood out to me was the danger of numbers averaging out the human experience – a challenge with digital humanities approach, as, at the same time, numbers can give great insights into history. Maybe this is a very good reason why those who create tools and those who use them benefit from a shared understanding.

“All archaeological excavation is destruction”, so what actually lives on is the record you create, says Dr Stuart Campbell. Traditional monographs synthesize all the data. They represent what is created through the process of excavation. It is a very conventional approach. But things are changing and digital archiving creates new ways of working in the virtual world of archaeological data. Dr Campbell made the point that interpretation is often privileged over the data itself in traditional methods, but new approaches open up the data, allowing more narratives to be created. The process of data creation becomes apparent, and the approach scales up to allow querying that breaks out beyond the boundaries of archaeological sites. For example, he talked about looking at pattens on ancient pottery and plotting where the pottery comes from. New sophisticated tools allow different dimensions to be brought into the research. Links can now be created that bring various social dimensions to archeological discoveries, but the understanding of what these connections really represent is less well understood or theorised.

Seemingly a contrast to many of the projects, a project to recreate the Gaskell house in  Manchester is more about the physical experience. People will be able to take books down from the shelves, sit down and read them. But actually there is a digital approach here too, as the intention is to add value to the experience by enabling visitors to leaf through digital copies of Gaskell’s works and find out more about the process of writing and publishing by showing different versions of the same stories, handwritten, with annotations, and published. It is enhancing the physical experience with a tactile experience through digital means.

Manchester is more about the physical experience. People will be able to take books down from the shelves, sit down and read them. But actually there is a digital approach here too, as the intention is to add value to the experience by enabling visitors to leaf through digital copies of Gaskell’s works and find out more about the process of writing and publishing by showing different versions of the same stories, handwritten, with annotations, and published. It is enhancing the physical experience with a tactile experience through digital means.

To end the morning we had a cautionary tale about the vulnerability of Websites. A very impressive site, allowing users to browse in detail through an Arabic manuscript, is to be taken down, presumably because of changes in personnel or priorities at the hosting institution.The sustainability of the digital approach is in itself a huge topic, whether it be the data or the dissemination approaches.